Download the white paper here »

In this Greycourt White Paper Wendy Pan tracks the extraordinary rise and more recent constraints on entrepreneurialism in China and considers its implications for Chinese private markets – and for the vitality of the Chinese economy as a whole.

Investors are justifiably worried about recent events in China. Many of the most concerned have already made the decision not to make new long-tailed investments in the country.

However, for those still weighing what to do, we consider below whether illiquid private investment funds in China (which have lock-up periods of ten years or more) still make sense. Note that we draw a contrast between investing in China’s liquid public stock market and investing in illiquid private equity (PE) and venture capital (VC) funds in China. The latter tends to focus on commitment to the country’s technology and consumer sectors for an extended period.

This paper attempts to describe the changing entrepreneurship landscape in China and its impact on PE/VC market. Should investors continue to support GPs who have historically generated good returns, especially now that China investment dollars are scarce? Or should evolving investment-related concerns in China suggest that investors look elsewhere?

We believe that the near-term investment outlook for technology sector and adjacent sectors in China will not approach recent historical performance.

Growth in China’s technology sector and adjacent sectors (edtech, consumer tech, fintech) has significantly slowed due to a confluence of internal and external factors. We believe that the near-term investment outlook for these sectors will not approach recent historical performance due to the unprecedented concentration of power at the highest level of the Chinese government and the hostility of those in charge to the private sector.

Institutional private equity investing in China began in the early 2000s and has experienced remarkable expansion over the last twenty years. Following China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO), the nation embraced foreign private equity investors. Notable milestones include the establishment of the Shenzhen SME board for initial public offerings (IPOs) in 2004 and the introduction of the ChiNEXT board in 2009, aimed at facilitating capital raises for high-tech enterprises.

Mercer, an investment consultant, reported that China’s PE/VC activities from 2016 to 2020 had doubled compared to the prior half-decade. In 2019, McKinsey predicted that China’s PE/VC market, as a portion of GDP, could surpass both the United States and Europe, potentially reaching 30% by 2030.[i]

A series of crackdowns on China’s tech sector have arguably unwound the entrepreneurial ecosystem that China painstakingly built over four decades.

However, after supporting private sector growth and entrepreneurship for many years, the Communist Party of China has shifted gears to curb the growth of the country’s private sector – especially the tech start-up sector.A series of crackdowns on China’s tech sector have arguably unwound the entrepreneurial ecosystem that China painstakingly built over four decades.

This was further exacerbated by America’s hawkish stand towards Chinese tech start-ups. Facing battles on both fronts, domestically and abroad, many wealthy Chinese have chosen to retire, and some have even moved abroad.[i]

We believe that the main driver of outsized returns for venture capital and private equity investments in China in the past – tech entrepreneurship – will be difficult, if not impossible, to repeat. We view this as a structural change and not a temporal one.

Entrepreneurship played an instrumental role in propelling private equity success in China, acting as the driving force behind the nation’s exponential growth from 1980 to 2020. Beginning with the end of the Cultural Revolution and China’s reintegration into the global community, a vibrant entrepreneurial ecosystem took shape. However, this ecosystem has experienced a gradual weakening due to the consolidation of political power at the highest levels over the past eleven years.

During the last three years, and especially in 2021, a series of crackdowns targeting private technology companies have sent unfavorable signals to international stakeholders and triggered a palpable chilling of investor sentiment. Stephen Roach, former chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia, wrote that, “For whatever reason, Chinese authorities are now using the full force of regulation to strangle the business models and financing capacity of the economy’s most dynamic sector.”[i] He concluded that the consequences of such actions could be dire to the animal spirits that propelled the country for many decades.

China’s political landscape underwent a transformation under Xi Jinping as its governance system assumed a more centralized structure. Prominent entrepreneurs in the technology sector, who were previously vocal advocates for the nation’s ongoing openness and had supported a transition toward greater democratic values, came to be perceived as threats to the Party’s cohesion or to Xi’s position within the country.

It is worth noting that this shift in the political landscape was primarily an internal development, in contrast to the belief held by many in the West (and the Communist Party’s rhetoric) that external factors, such as U.S. technological sanctions, were the principal drivers behind China’s structural decline in the realm of private enterprise.

Before we examine the effects of recent Chinese government crackdown on the technology sector in 2021, we will revisit some of the most prominent private enterprises built in the country and the entrepreneurs behind these powerhouses.

For four decades since Deng Xiaoping opened China to the world, the guiding principle of the Communist Party on economic development front was that “the nation is in a period of strategic opportunity, facing no imminent risk of conflicts.” This guiding principle allowed the bureaucrats and Communist party top officials to focus on economic development. In 1992, during his renowned tour of Shenzhen, a special economy zone now home to Chinese internet giant Tencent, Deng specifically advised local officials that a subset of the population should attain wealth before the pursuit of common prosperity could be realized. This guiding tenet catalyzed entrepreneurship in China.

Deng’s focus on economic development provided a fertile environment for the growth of China’s private sector. It nurtured the belief among the first generation of entrepreneurs that personal backgrounds were immaterial – diligent and intelligent work could pave the way to business success and affluence.

Success came not only in the technology sector, but also across consumer, industrials, real estate, healthcare, and other sectors, resulting in a substantial boom and producing a host of “what many consider world-class enterprises”, including:

These were both wildly successful entrepreneurs and also remarkable individuals: Jack Ma left a Chinese government-owned company to found Alibaba and is regarded as a pioneer in e-commerce worldwide; Pony Ma grew Tencent to a $500 billion market value, the first Asian company to reach such a valuation; Yu Minhong grew up in a rural village and failed his university entrance exams multiple times, but by 2016 his company was tutoring more than 26 million students; Wang Jianlin started a real estate company from a small bank loan but became Asia’s richest person in 2016; Zhang Yong didn’t eat in a restaurant until he was nineteen but grew his restaurant chain to more than 400 units employing 60,00 people; perhaps most remarkable of all, Zhou Qunfei was raised in poverty by a disabled father but became the world’s wealthiest self-made woman in 2016. This first generation of entrepreneurs also played an active role in civil society. Jack Ma, Yu Minhong, and Hugo Xiong hosted “Win in China,” a show akin to the American program “Shark Tank.” This period came to be recognized as the “gold rush for Chinese start-ups,” evidenced by the overwhelming response with over 150,000 entrepreneurs applying to participate in the “Win in China” show in 2008.

On the financing side, early iconic companies in the Chinese tech sector founded by the first generation of entrepreneurs were active investors in the subsequent start-up ecosystem. According to the World Economic Forum, BAT (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent) have invested in 80% of Chinese start-ups. Getting funded by some of these large companies and supported by these founders added significant credibility to a start-up.[i]

Riding this first wave of growth across the technology and multiple adjacent sectors, venture capital firms that were set up in China during late 1990s through the late 2000s generated outsized returns for their limited partners. IDG Capital China, Sequoia Capital China, DCM China, CDH Investments, Hillhouse Capital and Qiming Venture Partners are some examples of PE/VC firms that benefited from success of the first generation of entrepreneurs.

The second generation of entrepreneurs, born mostly in the late 1970s or early 1980s, also built great companies and great wealth for themselves:

Following on their initial success, PE/VC investors doubled down on the country from 2010-2020. They caught the second wave of the country’s growth and, according to McKinsey, fundraising for PE firms operating in China grew at a compound annual rate of 29% between 2009 and 2019. By 2019, China became the third largest PE market in the world. [i]

For many years there was a prevailing belief that the Chinese Communist Party would persist in prioritizing economic growth to support its emerging middle class and solidify the Party’s position as the ruling authority. While some controls were in place, they were not perceived as posing a significant threat to the broader entrepreneurialism ecosystem.

The period from 2020 to 2023 has witnessed a series of events that unmistakably signal a 180-degree shift in the Party’s priorities.

However, the period from 2020 to 2023 has witnessed a series of events that unmistakably signal a 180-degree shift in the Party’s priorities:

A crackdown on Ant Financial, a fintech affiliate of Alibaba Group. Two days before the firm’s anticipated trading date, Chinese regulators halted its IPO. This event was widely regarded as a pivotal turning point in the government’s stance toward private technology companies and their founders. Jack Ma disappeared from public view for over a year.

In 2021 Wang Xing, CEO of Meituan, posted a poem on social media that was interpreted as a critique of the government’s tech crackdown. Meituan then faced investigations from multiple authorities and shed $60 billion of market value.[i]

In 2021 DiDi proceeded with an IPO and listed on the NYSE, defying Chinese government guidance. DiDi subsequently lost 44% of its value after being de-listed from Chinese App Stores. It was also fined $1.2 billion.

China’s edtech industry, well-supported by Western venture and PE firms, was dealt a near-fatal blow when the Communist Party required all tutoring companies to re-register as nonprofit organizations. The crackdown erased an estimated $400 billion off the value of US-listed Chinese firms.[ii] In the summer of 2021 Chinese media began to denounce gaming as “spiritual opium,” leading to the closure of about 14,000 small gaming enterprises. Industry giant Tencent was forced to lay off workers and divert resources away from China and toward Singapore.[i]

Collectively, these events highlight a significant shift in the Chinese government’s approach, indicating that priorities have pivoted from focusing on economic growth to exerting greater control over the private sector. As one emerging markets manager put it, “They [Chinese entrepreneurs] need to know that the people who allowed them to get rich are no longer there.”[i]

In January 2021, Xi changed the party’s guiding principal on economic development from “letting a small portion of the population to get wealthy first” to “common prosperity.” In his opening address to the Party Congress in October 2022, Xi announced the slogan, “National security is the foundation of national rejuvenation.” This slogan was eerily reminiscent to entrepreneurs of the Cultural Revolution era when anyone could be “re-educated” for being a threat to national security.

An article titled “The End of China’s Economic Miracle,” in Foreign Affairs, encapsulated the dilemma confronting private sector entrepreneurs: “When an autocratic regime deviates from the previously understood ‘no politics, no problem’ understanding, the economic consequences are far-reaching. Faced with uncertainty beyond their control, people try to self-insure.” [i]

Amongst trade pressures, increased debt to GDP levels, and high youth unemployment, curbing the growth of private sector entrepreneurs significantly tempered China’s growth momentum. The consequence is a lack of consumer and business spending, even with ample stimulus measures, as we witnessed thus far in 2023.

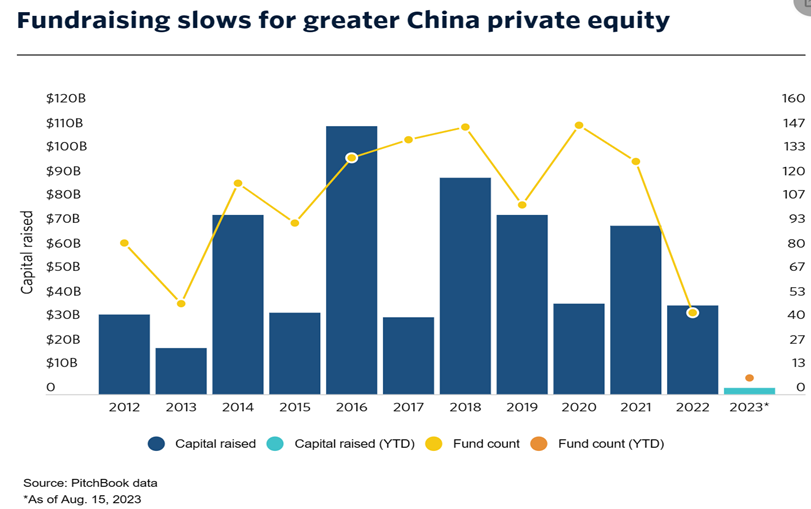

According to Pitchbook, there have been just nine private equity China-focused fund closes in 2023 (from January to August), raising a collective $2.7 billion, which would be the lowest total

for the past decade.[i] Only 19% of Preqin survey respondents cited China as an appealing investment destination at the end of 2022, down from 49% in November 2021. This shift in sentiment underscores the complex challenges and uncertainties that currently surround China’s investment landscape.

As China’s relationship with the West – and especially the US – deteriorates, investors’ decisions become further complicated. An escalating trade war and Chinese support for Russia in Ukraine are merely two of the tensions driving the two countries apart. In addition, it has become harder for Chinese companies to list on American stock exchanges. At the same time, the Biden Administration has placed limits on the ability of American investors to invest in China in certain sectors, including AI, quantum computing and semiconductors. According to market research firm Rhodiam Group, foreign direct investment in China fell to $20 billion in the first quarter of 2023, compared with $100 billion in the first quarter of 2022. [i] These developments highlight the complexity of the interplay between geopolitics, regulatory measures, and investment decisions, shaping the trajectory of asset owners’ involvement in the Chinese tech startup landscape amidst a challenging geopolitical backdrop.

We believe that entrepreneurialism, the predominant driver behind the remarkable returns observed in China’s PE/VC funds from 1990 to 2020, is experiencing constraints under the prevailing political regime. Compounding this, the assertive stance of the US towards China has further exacerbated the nation’s isolation in terms of both technological access and capital inflow from Western countries. Even as valuations fall in private markets in China, there might not be a fast recovery of multiples in the immediate future to compensate investors looking to “buy low” across their entire China private portfolio. Nonetheless, opportunities could surface in small pockets of the market for opportunistic investors.

Given these multifaceted dynamics, investors may wish to exercise restraint when it comes to PE/VC exposure in China.

As a result, long-term capital commitments originating from American sources and invested in China would encounter heightened return volatility, uncertainty regarding liquidity, and potential enduring impairment. Given these multifaceted dynamics, investors may wish to exercise restraint when it comes to PE/VC exposure in China.

NOTES

[i] Asia’s future is now | McKinsey

[ii] Global Migration Report by Henley & Partners

[iii] China’s Animal Spirits Deficit by Stephen S. Roach – Project Syndicate (project-syndicate.org)

[iv] The 3 pillars of China’s booming start-up ecosystem | World Economic Forum (weforum.org)

[v] In search of alpha: Updating the playbook for private equity in China | McKinsey

[vi] Meituan Stock Dives 15% After China Issues Food Platform Curbs – Bloomberg

[vii] Beijing is killing Chinese ed tech – Protocol

[ix] This individual chooses to remain anonymous.

[x] The End of China’s Economic Miracle | Foreign Affairs

[xi] Chinese private equity navigates choppy waters | PitchBook