Download the white paper here »

In Part 1 of “Compared to what?”, we considered what constitutes a useful benchmark and described several portfolio-level benchmarks (see Appendix A) we use at Greycourt: a Risk-adjusted Benchmark (“RAB”), a Strategic Benchmark, and a Tactical Benchmark. Each allows us to ask and answer useful questions:

Part 2 considers what conclusions we can reach by comparing various benchmarks to one another. For example, we can answer questions such as:

| Comparing | Isolates value of: |

| Actual vs. Risk Adjusted | Overall advice |

| Strategic vs. Risk Adjusted | Portfolio design |

| Actual vs. Tactical | Manager selection |

| Strategic vs. Tactical | Tactical positioning |

Answers to these questions allow an investor to determine which aspects of portfolio management are working well and which are not. In the end, this might highlight opportunities to improve portfolio and wealth outcomes. Comparisons of these three benchmarks, in conjunction with actual portfolio performance, can provide four potentially insightful comparisons:

Did our advisor deliver returns better than we could have achieved simply and cheaply on our own?

Comparing actual portfolio results to a similarly risky mix of passive stocks and bonds (the Risk-Adjusted Benchmark or “RAB”) allows us to determine if our investment advisor delivered returns better than that we could have achieved on our own simply and more cheaply via low-cost index funds and ETFs.

A note on the concept of defining a “similarly risky” portfolio: we think the best way to do this is by asking the question “how much risk am I intending to take through my portfolio’s design?” where we are defining risk as volatility. We regress the anticipated returns and correlation of two easily and cheaply investable asset classes – global stocks and bonds – to match the desired risk of a given portfolio design. For example, a portfolio design that is itself simply 60% global equity and 40% bonds would yield a similarly constituted risk-adjusted benchmark. But another portfolio that comprises 60% venture capital (a very risky form of equity) and 40% bonds would likely regress to something that looked more like an 80% global equity / 20% bond Risk Adjusted Benchmark.

This comparison of actual returns versus RAB returns yields a simple yes or no answer to a critically important question: was the effort to invest in a broad mix of asset classes via a strategic portfolio design, select good managers to bring that design to life, and periodically adjust portfolio positioning in an effort to be “tactical” actually additive? The answer sheds light on the question of whether paying for advice has been worth it!

Examining various combinations of the three benchmark comparisons provides insights as to where and why value was or wasn’t created.

Comparing the RAB to the Strategic Benchmark isolates the value added through the strategic asset allocation process. Did investing across a wider swath of asset classes allocated “optimally” add or detract value? In other words, “What is the value of strategic portfolio design?”

As Nobel laureate Harry Markowitz once noted, “diversification is the only free lunch in investing.” We now can begin to isolate the exact value added from increasing the portfolio’s diversification amongst asset types.

In addition to allocating across a wider array of investments to seek diversification benefits, a portfolio can deviate from the RAB by intentionally over- or under-emphasizing asset class components (“segments”) that the investment advisor believes will produce better/worse long-term returns than a simple capitalization-weighted portfolio of public stocks and bonds. For example, today many Greycourt advised portfolios intentionally have a slightly greater strategic target weight to less expensive US small cap equities than is implied by their weighting in a global equity index.

Many readers will note that the aim of sophisticated portfolio design is not necessarily to generate a higher absolute average annual return versus a portfolio that simply holds stocks and bonds. The goal is more accurately framed as seeking a more “efficient” portfolio that can produce the same amount of return for lower risk – again defining risk through the narrow lens of volatility. This is worth keeping in mind when considering how much value add comes from portfolio design: to fairly judge, it is important to look at compound annual growth rates – geometric returns – that account for volatility.

Did our managers outperform capitalization-weighted passive options?

The Tactical Benchmark reflects how the portfolio would have fared had it been invested in passive indices at actual portfolio weightings. Comparing the Tactical Benchmark to actual portfolio thus isolates the value added or detracted from selecting and sizing specific managers.

Manager selection is a broader concept that not only considers whether a manager outperformed its benchmark, but also asks whether the fees were worth it. Did a complicated strategy perform better than a simple one? Manager selection also incorporates the decision as to whether to deviate from long-only strategies, those that favor growth over value, and other considerations.

As with portfolio design, there are important considerations in measuring and interpreting the impact of manager selection and sizing. One of the most important is that many benchmarks utilize uninvestable index returns that are devoid of any kind of fees, even the low level of fees present in passive investment options. For this reason, it’s important to consider the drags that emerge in any real-world portfolio – not just whether larger management fees (and sometimes incentive fees or “carry”) are worth it but also the potential impact of trading costs and taxes.

Finally, comparing the Strategic Benchmark (i.e., passive indices allocated at target weights) to the Tactical Benchmark (i.e., passive indices allocated at actual weights) isolates the value added from tactical allocation decisions. A tactical allocation decision is one where there is an intentional deviation from long-term strategic targets. These deviations can come from believing an asset class is temporarily “cheap” and thus deserves to be overweighted or as a matter of circumstance, such as when a portfolio is being deployed over time following a large liquidity event.

Asset class sizing is an important, but under-discussed, portfolio management tool. It requires formulating a short-term opinion as to the relative value of various asset classes. How large should the sizing of this decision be? How should it be expressed? What are the tax implications of implementing this opinion and are they worth it?

Successful tactical decision making requires a complex understanding of capital markets and the ability to execute in a timely manner. No small feat – and one that should be undertaken with a great deal of intellectual humility and skepticism, recognizing that many forms of tactical positioning amount to glorified market timing.

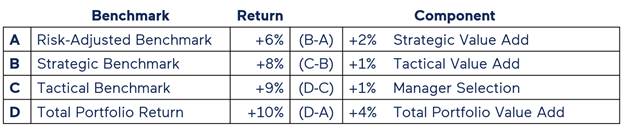

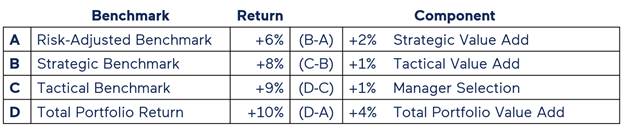

In the illustration below, a hypothetical portfolio returned 10% compared to a risk-adjusted benchmark return of 6%. You can see how using the three benchmarks together can be used to determine the impact on portfolio performance from strategic decisions, tactical positioning, and manager selection.

Thoughtful portfolio oversight requires consideration of the portfolio’s relative performance. Unsurprisingly, determining if the portfolio’s performance is “good” is a multi-layered question.

Determining whether a portfolio is achieving its overarching objectives over the long-term is the most critical determination. These objectives can include return hurdles above inflation, achievement of distribution and wealth transfer objectives, but relative return comparisons are also paramount to the decision-making process and evaluation of the efficacy of an overall investment strategy.

These more absolute return evaluations are best complemented by a relative measure which considers alternative investment approaches. A well-executed benchmarking strategy provides this point of comparison. As we have explored over these two white papers, using benchmarks with increasing levels of granularity allow investors to understand more deeply what is driving portfolio performance. And most critically, help in the decision-making process that can influence prospective positive portfolio outcomes.